A New Vision

After William Rankins Jr. went blind, we helped him see his way through daily life.

By Brian Vuyancih

William Rankins Jr. always had a gift for seeing things a certain way. He would see something that moved him and then draw it — sometimes on a pad of paper or a canvas — and sometimes on the side of a building. If you’ve ever been to downtown Cincinnati, you’ve probably seen his work. He was paid to get your attention after all, or inspire you in some way. William Rankins Jr. is an artist — a muralist to be more specific — one of the first in Cincinnati and highly sought after during his time. Some call him iconic. For decades, he adorned urban life in Cincinnati with his paint and his vision. Until he went blind.

“I’ve always been able to draw,” William said. I was born that way — I was blessed.”

He grew up in Evanston in the 1960s, and he completed his first work of art when he was five years old. It was the Pillsbury Doughboy, and he penned it on his mother’s bathroom wall. His payment? “I got paid with that belt,” William said laughing. After his whooping and a closer inspection, his parents came to their senses when they noticed how good his piece of mischief looked. From that point on, they recognized his gift and nurtured his talent.

“For Christmas I never got any real toys. I got color by numbers sets, drawing pads, pencils,” William said. His father, who worked at Gibson Greeting Cards in Roselawn would bring home scraps of cardstock for William to draw on.

If only his teachers would have fully understood him in the same way. “I tended to get into trouble for drawing on my desk,” William chuckled. He doesn’t know why he drew a picture of Jimmy Carter coming out of a peanut one day, but that one actually earned him some coverage in a magazine and breakfast with the board education.

Right out of high school William entered the Navy. When he got back home, he earned a living hanging drywall as a remodeler. In fact, his first commissioned murals were painted on the same drywall that he hung in people’s houses. Imagine a vista of waterfalls, lakes, and forests painted on all four walls of a room. That is how it all started.

Right out of high school William entered the Navy. When he got back home, he earned a living hanging drywall as a remodeler. In fact, his first commissioned murals were painted on the same drywall that he hung in people’s houses. Imagine a vista of waterfalls, lakes, and forests painted on all four walls of a room. That is how it all started.

It wasn’t long until news of William’s talent started to spread by word of mouth. William calls it the domino effect. That’s when your work earns you more work, and that work earns work, and so on. Soon gas stations, drive-thrus, nightclubs, daycares, buses, and limousines would all receive the mark of William’s paintbrush. Even Jungle Jim Bonaminio hired William to add some attention grabbing visuals to one of his early corner produce stands.

By the 1990s William was leaving his mark on Cincinnati culture. His murals began to sprawl entire buildings. Malls and attractions, including King’s Island, were among just some of his clients. Even the Art Consortium downtown represented itself through William’s work. William took particular pride in a piece dubbed “The Mural of Soul” by the local media. It was an ensemble of renowned musicians painted on the side of PJ’s Lounge at the corner of McGregor Avenue and Reading Road in Cincinnati.

At the corner of Race Street and Liberty Street in Over-the-Rhine, a mural painted by William pointed passersby in the direction of a small but popular food truck of sorts called Ollie’s Trolley. The piece, which depicted a collage of visuals including a giant hotdog, a likeness of William’s son, and an image of pop culture icon Steve Urkel, became a topic of controversy a few years ago when the mural was set for removal to accommodate renovations for the building that hosted it. The community fought to preserve it, but the renovations moved forward and William’s mural disappeared.

It was in the early 2000s when William started to notice trouble with his eyesight. His peripheral vision went first leaving him with only a circle of focus within the center of his vision. “Then that circle got smaller and smaller and smaller,” William explained. It was glaucoma — damage to the optic nerve due to pressure in his eyes. Then in 2014, William suffered a stroke which finished the damage the glaucoma had already started, leaving him with virtually no sight.

It was in the early 2000s when William started to notice trouble with his eyesight. His peripheral vision went first leaving him with only a circle of focus within the center of his vision. “Then that circle got smaller and smaller and smaller,” William explained. It was glaucoma — damage to the optic nerve due to pressure in his eyes. Then in 2014, William suffered a stroke which finished the damage the glaucoma had already started, leaving him with virtually no sight.

“I can see shadows,” William said slowly waving his hand in front of his face. “It’s like I’m in a deep fog; I can see the shape of my hand, but I can’t see any detail.”

“It hurt me really bad,” William said. “It hurt me really bad,” he repeated, but quieter. “Art was my passion. It was the legacy I was building for my kids and my grandkids. All I could say is Lord you know what you’re doing. But I didn’t cry about it. It ain’t going to do me any good to cry. People ask me, ‘How do you do it?’ But what am I supposed to do? You have to just suck it up.”

Today William lives in an apartment in Springdale with his service dog, Donnie, a 105-pound Labrador Retriever. “She’s my eyes,” he said patting her on her head. Donnie sat in front of William faithfully.

“I’m not a quitter though,” William noted. He says that blindness gave him a new perspective; he calls it an inner-vision. “I can see things that you can’t see,” he added. He said he doesn’t take things for granted anymore and admits that things could be worse. His inner-vision, as he described it, seems to be a transition from the outward to the inward, from self-expression to self-reflection, and when it really comes into focus, he can see deeply within himself.

“I walk by faith now, not by sight.”

Deborah Clinkscale visits William several times per month. He considers her a friend — or in his own words: a godsend. She’s an independent living assistant assigned to William through Meals on Wheels. She’s actually the Senior Services Manager. Her job when she’s with William is to guide him through paying his bills and help with other paperwork and personal affairs. She’s not a medical professional, but she does help him schedule his medical appointments and oversees his mounds of healthcare paperwork.

Deborah also inspires William to keep painting.

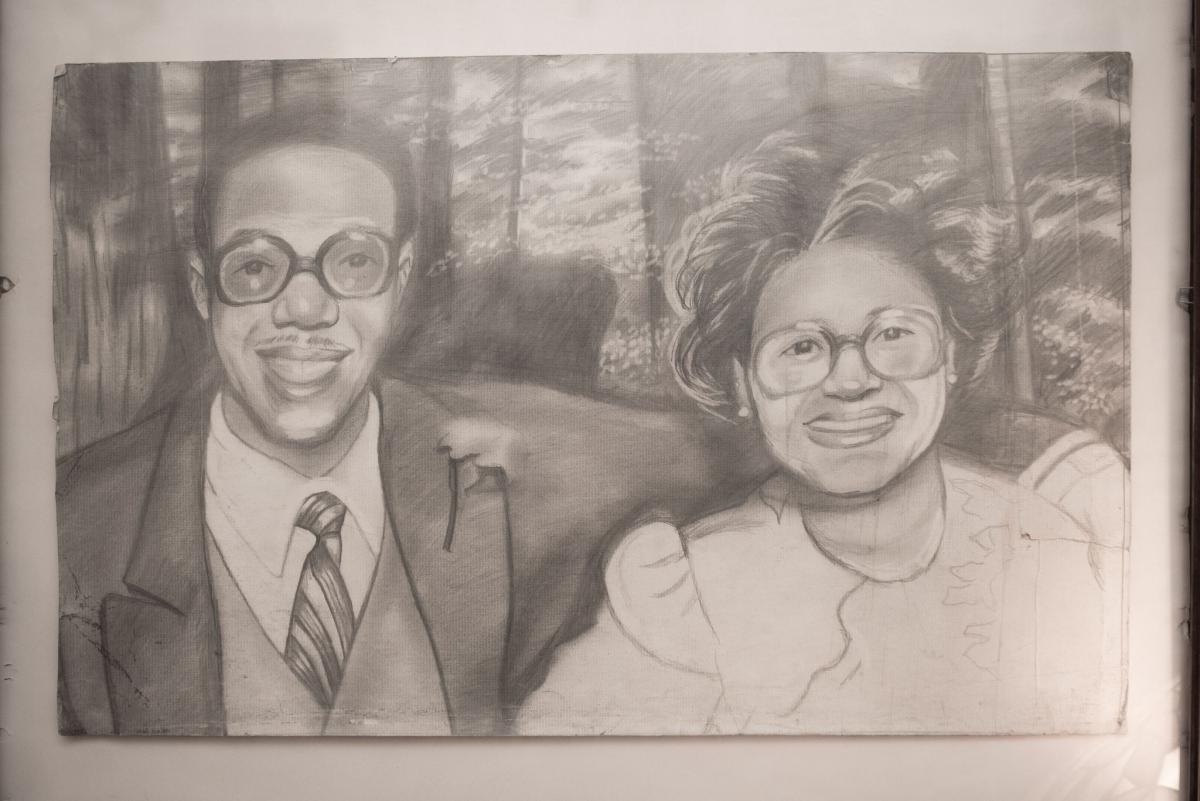

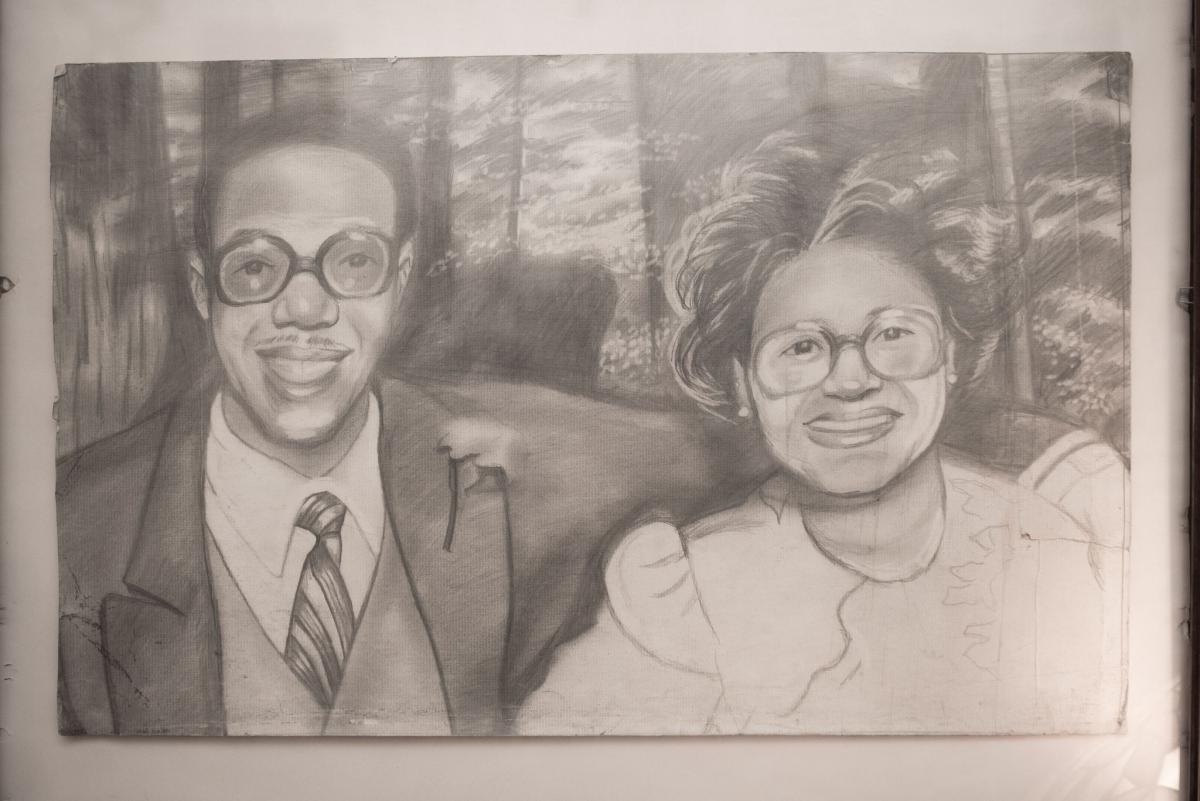

It was a month ago when Deborah stood next to William in his apartment. She had already bought the paint and the canvas and the other supplies. He would tell her what color he needed, and she would lead his brush to it. “I need a gray,” William would say, and she would tell him to add more black or white directing him still. William could see the waterfall in his head. Faces were fading in his mind, but nature stayed true. It took him about a week to finish the piece; an icy waterfall emerging from a shadowy landform. The cold water below breaks up in hues of blue and gray. Behind it all in the background is a sky of clear blue and a single soft white cloud.

Deborah said the experience was humbling and marveled at how well William has adapted to his struggle. William called her an inspiration. You can sense a bond between them when they talk. He teases Deborah about the time she wasn’t paying attention and asked William to look at something. They both still laugh about it like old friends.

William was asked a hypothetical question: If he could regain his eyesight for just one hour, what piece of his own work would he want to see again? “All of them,” he said initially. But there was one piece he kept going back to. He gave it away to a friend long ago, but hopes to obtain a copy to give to Deborah as a gift. William described it from memory as a picture of Jesus. He said it was in black and white and sketched in pencil. Jesus’ head hung low and defeated. The crown of thorns dug deep into his scalp and the blood washed over his face. His eyes were closed, but he wasn’t afraid.

“I’ve always been able to draw,” William said. I was born that way — I was blessed.”

“I’ve always been able to draw,” William said. I was born that way — I was blessed.” Right out of high school William entered the Navy. When he got back home, he earned a living hanging drywall as a remodeler. In fact, his first commissioned murals were painted on the same drywall that he hung in people’s houses. Imagine a vista of waterfalls, lakes, and forests painted on all four walls of a room. That is how it all started.

Right out of high school William entered the Navy. When he got back home, he earned a living hanging drywall as a remodeler. In fact, his first commissioned murals were painted on the same drywall that he hung in people’s houses. Imagine a vista of waterfalls, lakes, and forests painted on all four walls of a room. That is how it all started. It was in the early 2000s when William started to notice trouble with his eyesight. His peripheral vision went first leaving him with only a circle of focus within the center of his vision. “Then that circle got smaller and smaller and smaller,” William explained. It was glaucoma — damage to the optic nerve due to pressure in his eyes. Then in 2014, William suffered a stroke which finished the damage the glaucoma had already started, leaving him with virtually no sight.

It was in the early 2000s when William started to notice trouble with his eyesight. His peripheral vision went first leaving him with only a circle of focus within the center of his vision. “Then that circle got smaller and smaller and smaller,” William explained. It was glaucoma — damage to the optic nerve due to pressure in his eyes. Then in 2014, William suffered a stroke which finished the damage the glaucoma had already started, leaving him with virtually no sight.